For a small country with only four hundred years of European influence, South Africa has a very rich literary identity. The difficulty of being able to present a list of the best South African authors is that the population is made up of multiple cultures, and speaks scores of languages. The country is unusual in that it has eleven official languages. The different communities are each, in turn, linguistically fragmented and some of the sub-groups that have grown out of the mixing of groups have developed new group identities. This rich demographic texture has thrown up an amazing variety of writers, particularly in the twenty-first century.

Where does this leave the selection of ten of the best South African writers? The list cannot contain just the Nobel Prize for Literature winners and those who almost made it to the Prize. Nor can one take the politically correct route and fill the list with young black writers at the expense of white writers of previous generations who may be better writers. And should a brilliant young Afrikaans poet, Ingrid Jonker, who people have compared with Sylvia Plath, one who committed suicide at the age of 32, before she could grow into a major poet, be ignored, to the advantage of the octogenarian Wilbur Smith who sold more books than almost any other writer?

Moreover, what about legends like Stuart Cloete, Laurens van der Post, Roy Campbell, Athol Fugard, Christopher Hope, C.J. Langenhoven, Etienne Le Roux, Eugene Marais? Not in our top ten South African writers but could have been.

With this context in mind, we have tried to use merit as the arbiter. Here is the list of best South African authors, in order of the writers’ date of birth:

Olive Schreiner, 1855-1920

Perhaps Olive Schreiner would not normally be included among the top ten South African writers, but her place is secure here mainly because of her extraordinary novel The Story of An African Farm. She is much out of fashion in South Africa today and her name almost taboo in some quarters because she lived and wrote in the colonial era and her novels and stories were concerned with life on the colonial frontier.

She was a literary giant of the pre-apartheid era. During the apartheid decades, many writers made their names as writers because politics was unavoidable and apartheid affected the lives of everyone: that inspired very strong, passionate writing. There were enough interesting political and social issues in Schreiner’s time for her to address.

Schreiner was concerned with several dangerous issues of her time – agnosticism, individualism, the professional aspirations of women, and the precarious nature of life on the frontier. She was far ahead of women of her time generally in that she was free of the shackles that tied women down to the assumptions of life in a patriarchal society. Her activities anticipated those of the anti-apartheid warriors to appear thirty years after her death. She was an advocate for the South African groups who were excluded from political power – jews, indians, and indigenous blacks, and she was an anti-war campaigner.

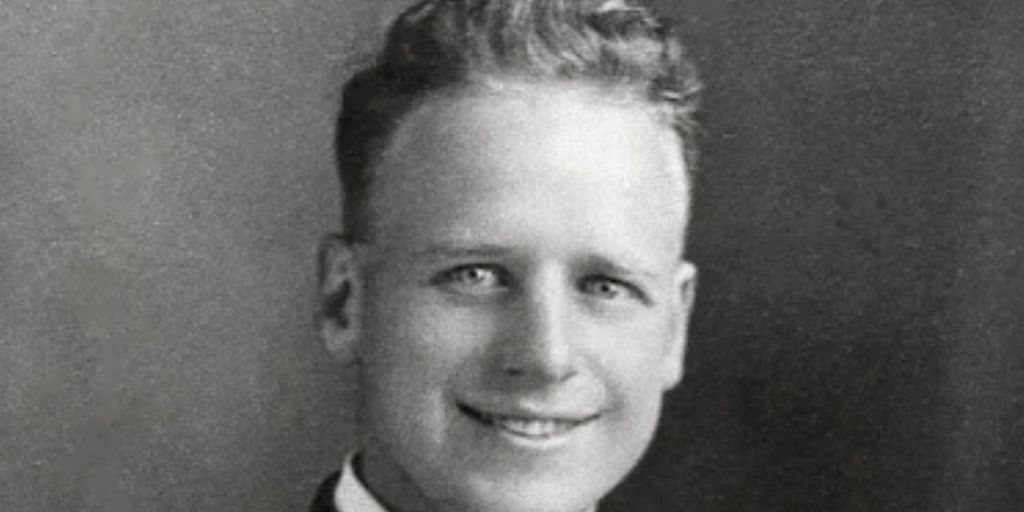

Alan Paton, 1903-1988

Alan Stewart Paton’s Cry the Beloved Country, about a tragedy that comes about as a result of South Africa’s racial policies, is the most famous South African novel. It was also the first to receive international acclaim.

In case anyone should believe the novel to be a one-off success, he followed it up with Too Late the Phalarope and several more. All his novels and short stories deal with the same theme – the oppressive government and its effects on ordinary people. Paton was a lifelong political activist, ruthlessly persecuted by the Nationalist government. He was a member of the Liberal Party, which was a banned organisation.

His novels still have resonance in a post apartheid world. Cry the Beloved Country has been twice adapted for film and several of his other works have been adapted for the stage and television as well. Paton was awarded the prestigious American Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Fiction in 1949 for Cry the Beloved Country. The award is dedicated to honouring written books that make important contributions to the understanding of racism and the appreciation of the rich diversity of human culture.

Herman Charles Bosman, 1905-1951

Herman Charles Bosman is our favourite South African writer. Why should that be with a cohort of such wonderful writers? It’s because of the sheer pleasure – no, joy – of reading his short stories. They are perfect, and to give an idea, one could think of Bosman as the Mark Twain of South Africa – charming stories, beautifully told, very simple on the surface, but with a firm bite beneath, using the deceptive devices of humour and irony.

They are all set in the remote rural community – the Groot (Great) Marico district, more or less cut off from the sophisticated city, and even town, life. There is a sprinkling of very simple, uneducated, white, Afrikaans, people who all know each other, some Khoi, some San, and some tribal Africans. An elderly patriarch narrates the stories, which are about the things that happen to the people in the community and the relationships between them in this mix, and in a simple way, with well-oiled storytelling with beautiful stories that just roll out effortlessly, some universal idea is revealed in each one. It’s brilliant writing.

After a university education, Bosman trained as a teacher and was sent to teach in the Marico, where he was later to set his stories. On a visit home during the holidays, he had an argument with his stepbrother and shot him dead. He was sentenced to death and spent some time on death row before his sentence was commuted to 10 years, of which he served 4. He then became a journalist in Johannesburg and later a theatre critic with The Times in London. His book, Stone Cold Jug, about his life on death row, is a must-read for humour, great storytelling, and information about a horrifying experience in a bye-gone age.

Nadine Gordimer, 1923-2020

One of the most prolific 20th century novelists and short story writers, Nadine Gordimer was the doyenne of South African literature until her death in 2014.

Her fiction sketched the multiple facets of South African society. Her writing reflects her political life – anti-apartheid campaigner, anti-censorship. The latter was particularly dear to her campaigning heart with the banning of several of her novels during the apartheid years. Her writing takes on the political issues of her time in prose that is a delight to read, being, as she was, a great story-teller. At the same time, it is epic in the same scope and tone as some of the best Russian authors – mixing Dostoevsky’s writing of characters with stories reminiscent of Chekhov. She won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1991.

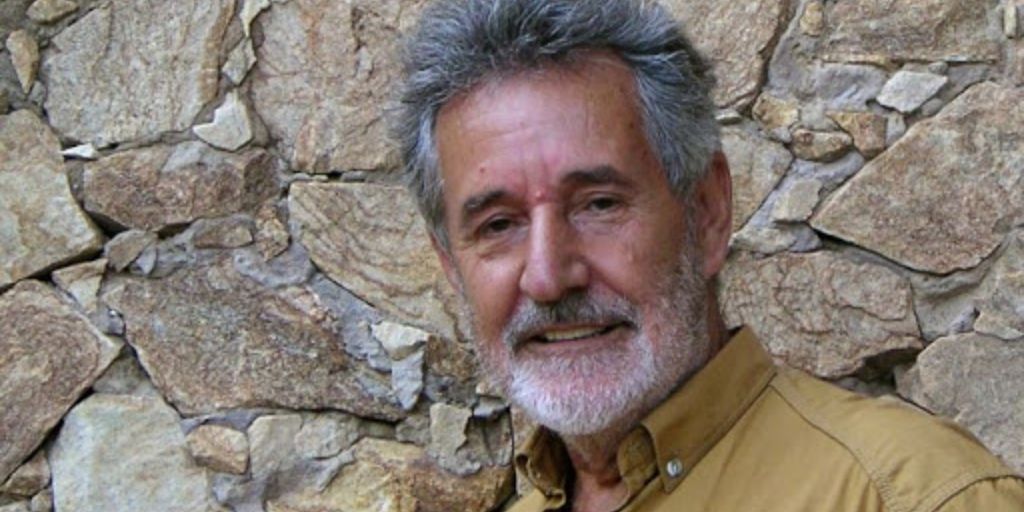

Andre Brink, 1935-2015

Probably the most famous and prolific South African writer, Andre Brink was a novelist and academic, ending his academic career as professor of English at the University of Cape Town. He began writing in Afrikaans, later writing each novel in both languages – not translations but writing in the two languages.

Brink was a leading figure in the 1960’s Afrikaans literary movement, ‘die destigers’ (the sixty-ers). Their idea was to speak out against apartheid in the Afrikaans language, and for that they were, of course, persecuted. Another aim was to bring European influences into Afrikaans literature which, up to this time, had been extremely parochial. When the apartheid era came to an end Brink’s work addressed the new range of issues confronting the new South African democracy.

Probably Brink’s most famous novel is A Dry White Season in which a white Afrikaner liberal investigates the death of a black activist in police custody. The 1989 film adaptation is worth watching. Big stars like Donald Sutherland and Marlon Brando offered their services free, along with some of South Africa’s biggest stars

Bessie Head, 1937-1986

South Africa and Botswana compete to own Bessie Head as she was born in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa but lived her later life in Botswana, although she never became a stranger to her homeland. Her novels and short stories are very personal and much of her writing is biographical.

Her own personal history is very much a South African story. She was born of an illegal union between a white woman and a black father, and abandoned by both, grew up in an orphanage. To escape an early, abusive marriage she fled to Botswana and settled in a remote village.

Her novels are about the survival of women with her kind of background, and also about traditional Botswanan rural culture. She maintained that literature should be a reflection of daily encounters with undistinguished people. Her works are exercises in empathy with neglected and abused women and children in South Africa and with those who govern – their greed and indifference

Breyten Breytenbach, born 1939

Breyten Breytenbach is an Akrikaner, regarded by many Afrikaners as the grandfather of South African poetry. He also writes novels and essays as well as being a visual artist. As a young writer he was part of a group of young Afrikaans writers, which included Andre P Brink and Ingrid Jonker, known as the ‘die sestigers‘ (the sixties). Although they were politically motivated they were literary writers and many of their books were banned. Breytenbach was imprisoned by the apartheid government and later emigrated to France.

His first novel, Sewe dae by die Silbersteins, written in Afrikaans, is quite a weird text that became famous within the small community of Afrikaans speakers in spite of its highly experimental style. It was later translated into English. Since then Breytenbach has gone international and has been writing in English for many years. His The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist is a revealing account of the South African prison system, based on the seven years he spent as a prisoner convicted of high treason.

J.M. Coetzee, born 1940

J.M. Coetzee is the foremost of South Africa’s many internationally acclaimed writers. His voice is unique and unfailingly fascinating. Experimental in his technique, he takes on the most politically sensitive issues facing the country. He is fearless in his hard-hitting approach to such things as race and class, and politics. He frequently creates a surreal, alien kind of setting in order to magnify the characters and the characteristics of South Africa. It is a broken country and his characters echo that in being broken themselves. The novels are full of dysfunction like drug-taking, drinking, and extreme violence. Coetzee was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2003.

Zakes Mda, born 1948

Mba is a Xhosa novelist, poet, and playwright and winner of major South African and British literary awards. He is also a musician and painter. His first novel, Ways of Dying, immediately got international attention. It catalogued the transitional years of his country as it moved from a police state to a democracy. Set in the violent urban landscape of an unidentified South African city it presents a vivid picture of life in the midst of the violence occurring in South Africa’s townships and squatter settlements. He continued to achieve success as he turned out new novels. Ways of Dying has been translated into 21 languages.

Njabulo Ndebele, born 1948

Njabulo Ndebele is a Zulu novelist and academic. His novels portray the ordinary people who live in the poverty-stricken townships around Cape Town. He is enjoying a distinguished academic career, having served as the Vice-chancellor and Principle of the University of Cape Town, and subsequently the Chancellor of Johannesburg University.

And that’s our pick of South Africa’s best writers. What’s your take – anyone missing from this list you think we should add? Let us know in the comments section below.

Most would tick my box. However, I would consider Eugene Marais, who writes beautifully on ethology and Monica Hunter/Wilson whose anthropology writings are a joy. (I am not much of a fiction reader).

By the way Too Late the Phalarope was a really gripping read – more so than Cry ….,